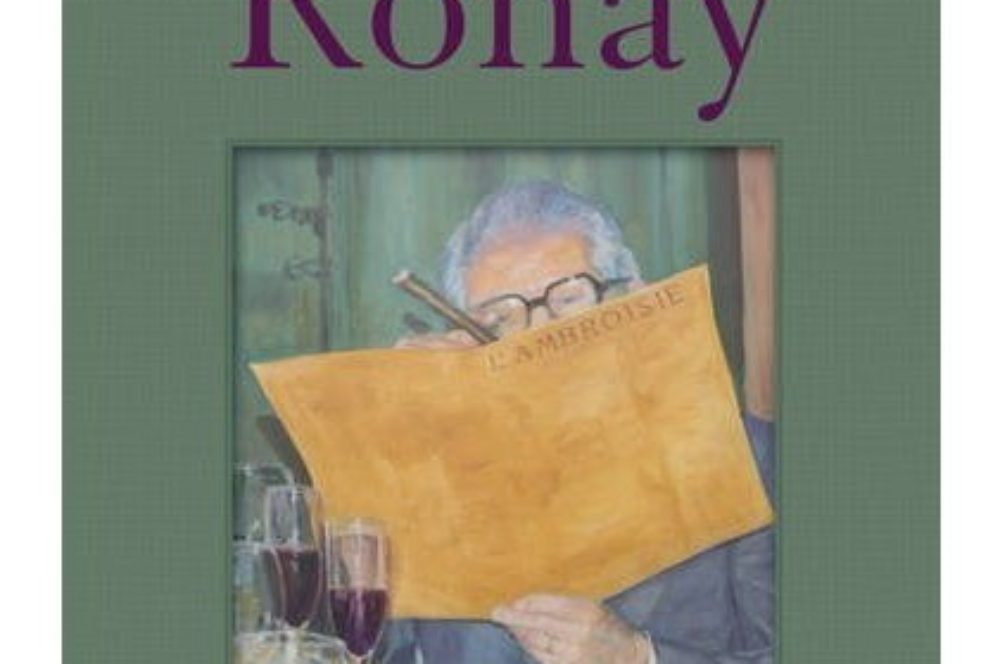

If you’re under 30 you’ve probably never heard of Egon Ronay

If you’re under 30 you’ve probably never heard of Egon Ronay

but for anyone eating out in the 1980s the Egon Ronay Guide and the Good Food Guide, were the must-have guides to eating out in the UK. In his day he was as famous as Fanny Craddock.

Ronay died in 2010 at the age of 95 and this book, edited and published by Peter Bazalgette is a tribute to him by friends and colleagues, members of the British Academy of Gastronomes, a private club created by Ronay ostensibly ‘to improve the standard of food and beverage at all levels of consumption across the UK’ though from this book you might think it was more of a toffs’ dining clique.

Members included Peter Bazalgette, Lord Bramall. Ronnie Corbett, Andrew Neill, Nick Ross and Sir Evelyn de Rothschild. They held extravagant dinners at which top chefs like Roux, Mossiman and Koffman cooked for them. Tom Jaine, a former Good Food Guide editor, derided them as ‘a self-appointed group of stomachs.’

Egon Ronay guides were popular for some 20 years until Ronay sold out to the AA, a move he was to bitterly regret. Me, too. The AA sold the name to another company for whom I did some work. I never got paid so, like Ronay, I sued and won but with no assets the company never paid up.

Ronay got his name back and brought out another couple of Guides after that. They made little impact but in it’s heyday a listing in the Egon Ronay guide could make a restaurant. In 1979 the Guide turned the McCoys into an overnight success by naming it Restaurant of the Year. ‘From 15 or 20 a night we were full with 60 and turning more away,’ recalls one of the McCoys.

Ronay always hit the headlines with his ‘peppery’ introductions to each guide in which he took on some travesty of British cooking like greasy British breakfasts, hospital food and most famously the awful catering atmotorway service stations which led to a Commission of Enquiry and a long running ding-dong with service station owner, Sir Charles Forte.

For the self-publicist and limelight hungry Ronay, media coverage was his life blood. It kept the Guides in the book shops and Ronay’s name in the papers. His empire grew to a staff of 50 and a turnover of £250,000 (£3.5 million in today’s money).

Each chapter of this book is written by a friend. An old school friend tells us how Ronay was born into a wealthy Hungarian family, how he would drink the best Champagne in his father’s elegant Belvarosi Café in Budapest. His World War II history is not entirely clear until Paul Fabry tells how in 1946 he helped Ronay forge his papers and flee to Britain where he stayed for the next 63 years. In London Ronay opened the Marquee restaurant next to Harrods and began writing restaurant reviews for the Daily Telegraph.

His solicitor describes a careful, hardworking man who ate well and exercised daily but ‘whilst he epitomised toujours la politesse, he also thrived on confrontation.’ Michael Edwards, one of his inspectors, describes him as ‘mercurial’ and at times ‘brutal and dismissive.’ In the end they all claim him as a much loved colleague and a friend. I wasn’t exactly convinced.

The last chapter is written by that infamous ‘stomach’ Michael Winner. He has a lesson for all of us who attempt to write about food and restaurants: ‘Food critics are the most useless critics in the world. None of them knows what they are talking about. They’re pompous, arrogant show-offs who write in overflowing sentences about sauces no one knows or cares about.’ Except of course his friend Egon Ronay… and himself.